This post was updated 2 Feb. 2014.

Happy new year to everyone! My new book, Mavericks of Sound, over 300 pages featuring an array of interviews and photos with roots and indie rockers from Merle Haggard to Pere Ubu and the Swans, has been accepted by an imprint of independent publishers Rowman and Littlefield. The book should be processed beginning in March 2014 and hopefully available to the public by the end of the year.

In the meantime, be sure to check out my new short but feisty interview with Joey Shithead of Canadian punk stalwarts DOA in the Houston Press.

You can also peruse an excellent review and overview of my book Left of the Dial, written by Steve Scanner, in the website Scanner Zine here.

My newest academic article, “Protest and Survive: the Praxis of Punk Politics,” has survived its first draft and is being submitted to journals for possible publication. Currently 25 pages, it includes new interviews with the likes of Mike Magrann of Channel 3 and Mark Anderson of Positive Force D.C., as well as a previously unpublished interview with Justin Sane of Anti-Flag, among others.

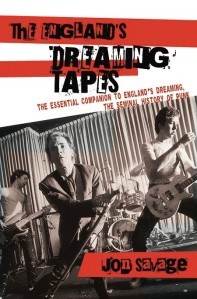

Below, I offer you an excerpt of an article I penned examining the work of punk historian Jon Savage. The link to the complete article can be found at the end of the segment.

Who Owns Punk History: Jon Savage, the England’s Dreaming Tapes, University of Minnesota Press

Originally published by Popmatters, 15 Dec. 2010.

Undoubtedly, punk still exists as a tantalizing music subculture that has expanded, mutated, and doubled-back, like a snake eating itself, in routine redux over the last 30 years, turning three garage rock chords and the so-called truth into nihilistic newer variations like D-Beat, crust punk, powerviolence, grindcore, and screamo. Recent anniversaries of Frontier Records (label to TSOL, Circle Jerks, and Suicidal Tendencies) and melodic punk stalwarts Bad Religion testify to long term trajectories and traditions; meanwhile, interpretations of the pose, language, style, and attitudes of punk have infected multiple academic disciplines from sociology and folklore to musicology and women’s studies. In purely commercial terms, punk has long been subdued and harnessed, reshaping retail commodity culturescapes. Faux-hawks, patches, studded bracelets, and skulls stitched on T-shirts have become common fashion accessories in bland suburbs and edgy barrios alike.

Undoubtedly, punk still exists as a tantalizing music subculture that has expanded, mutated, and doubled-back, like a snake eating itself, in routine redux over the last 30 years, turning three garage rock chords and the so-called truth into nihilistic newer variations like D-Beat, crust punk, powerviolence, grindcore, and screamo. Recent anniversaries of Frontier Records (label to TSOL, Circle Jerks, and Suicidal Tendencies) and melodic punk stalwarts Bad Religion testify to long term trajectories and traditions; meanwhile, interpretations of the pose, language, style, and attitudes of punk have infected multiple academic disciplines from sociology and folklore to musicology and women’s studies. In purely commercial terms, punk has long been subdued and harnessed, reshaping retail commodity culturescapes. Faux-hawks, patches, studded bracelets, and skulls stitched on T-shirts have become common fashion accessories in bland suburbs and edgy barrios alike.

The telling, not the mere examination—acts of theory and conjecture—of its convoluted history, grounded in memoirs, magazine exposes, blogs, and films, remains unstable, partial, thorny, and riddled with gaps. Certainly, seminal books have risen to the top of the heap. Many brim with oral history, which some readers believe fosters candor and authenticity. We Got the Neutron Bomb (Three Rivers Press, 2001) surveys West Coast punk while Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk (Penguin, 1997), by former PUNK fanzine editor Legs McNeil, helped by co-editor Gillian McCain, represents hard-boiled New York City. These quasi-journalistic romps featuring iconic talking heads reminiscing about their roles and first-hand experiences without much writerly fluff proved to be quite popular.

That modus operandi essentially makes this epic 752-page collection of compiled interviews by Jon Savage feel weighty and pertinent, even if one has already read his much-lauded England’s Dreaming: Anarchy, Sex Pistols, Punk Rock, and Beyond (St. Martin’s Griffin, 1992), which almost 20 years ago examined the zero hour of punk, mostly in England. Representing just a portion of his impressive archives for the text, these transcripts make readers feel like they are sitting at Savage’s side as he finesses rock ‘n’ roll rebels and forgotten helpers alike, though don’t expect many WikiLeak profundities dug from the minefields of memory. Plus, interviews with the likes of Ed Kuepper from The Saints and V. Vale, editor of vintage San Francisco Search and Destroy fanzine, remain available on http://www.jonsavage.com only.

The template formula is quite breezy, off-the-cuff, and anecdotal. More recent Do-It-Yourself texts, such as the reference books American Hardcore: A Tribal History (Feral House, 2001) and Going Underground: American Punk 1979-1992 (Zuo Press, 2006), both written by ‘80s scenesters, attempt to reflect a vast landscape of punk, but also have been heavily critiqued for their shortcomings; for instance, Randy “Biscuit” Turner, singer of the Big Boys, told me that the sections in American Hardcore… blurred and distorted details, relied on gossip, and misrepresented bands. Meanwhile, although “Biscuit” was featured on the cover of Going Underground…, he was not interviewed. He exists as an embellishment only—a mute icon—unleashing a protruding middle finger in the photograph akin to similar outlaw images of Johnny Cash.

Though academics have lauded Savage’s England’s Dreaming… as a nimble intellectual text, others equally detest it as well. Punk writer Stewart Homes dubbed Savage a cultural elitist who “shores up their theory by appropriating punk rock” while legitimizing Au Pairs and Gang of Four and ignoring street punk, which he seemingly judges as both laddish and loutish (Cranked Up Really High – Genre Theory and Punk Rock, Codex, 1995). In 2003, Captain Sensible of the Damned told me, “England’s Dreaming … is a ripe load of shit if you ask me. I much prefer Johnny Rotten’s No Irish, No Blacks, No Dogs (1995).” Additionally, Andy Czezowski, former proprietor of The Roxy, one of punk’s most prominent early clubs, aggressively admitted to the on-line journal 3: AM Magazine: “The guy’s a total wanker, constantly re-writing history to suit his own purposes… Just a shallow journalist really… totally peripheral guy. Always intellectualizing” (2003).

This new transcript-based format might be an avid antidote to such charges, for Savage doesn’t interpret, preen, or prettify. By avoiding rabbit holes of theory and pontification, he simply allows readers to indulge in these moments, like a fly on the wall. In that sense, these pages may offer up a common ground to all sides – a rich, interwoven series of conversations, unadulterated and sculpted only by his own keen and casual questions, including lengthy bits with both Sensible and Czezowski in raw, not boiled, form.

This new transcript-based format might be an avid antidote to such charges, for Savage doesn’t interpret, preen, or prettify. By avoiding rabbit holes of theory and pontification, he simply allows readers to indulge in these moments, like a fly on the wall. In that sense, these pages may offer up a common ground to all sides – a rich, interwoven series of conversations, unadulterated and sculpted only by his own keen and casual questions, including lengthy bits with both Sensible and Czezowski in raw, not boiled, form.

To be fair, no account of punk is bound to be error-free, without gaps, or even fully democratic. Don’t look for the likes of Chelsea, UK Subs, The Jam, and Slaughter and the Dogs in this volume. The old stand-by stalwarts, however, do offer scoops: Joe Strummer wholeheartedly illustrates the rundown, inner-city, squat-ridden, pre-Clash London era of the 101ers; wise and wily Johnny Rotten dispels the artiness of it all, reminding readers the Pistols were studio mongers akin to stadium rockers, layering a staggering multitude of guitar tracks on “Anarchy in the U.K.” (not that Bad Religion isn’t equally guilty); while Adam Ant flagellates the ludicrous pretensions, ala Rocky Horror Picture Show, of the Derek Jarman film Jubilee (1978), which featured an early line-up of his band, Gene October of Chelsea, gender bender American rocker Wayne County, and female iconoclast Jordan.

As for the Pistols, Johnny Rotten is cast as the aggravated adrogyne, Steve Jones as the illiterate trad-rock sex machine, Paul Cook as the blank faced unknown, Sid as the sweet kid swallowed by Nancy Spungen in a mythic downward spiral, and Glen Matlock as the effete middle-class popster. Part leftover fans of Small Faces, part Bay City Rollers boy band gone wild, part consumer warriors and art saboteurs, they staged their hit-and-run media blitz, and we’re still debating their worth.

To see the complete text, please visit Popmatters.