Interview with Marc H. Miller, co-curator of the infamous Punk Art Show with Bettie Ringma and co-editor of ABC No Rio Dinero: The Story of a Lower East Side Art Gallery with Alan Moore.

April 2012

How did you first become aware of the vivid nature of punk visual arts?

In the mid-1970s, New York was a mecca for artists, musicians, and other assorted creative types. Everyone lived in Lower East Side tenements and downtown lofts, which created a very fluid social scene where all the arts intermixed. It was a time of generational shift, the baby boomers were coming in and trying to find their place. Everyone — whether they were artists, musicians or whatever — confronted the same situation. Art galleries and record labels were booked solid with artists from the 60s. New arrivals were shut out and had to create their own scene and opportunities. The musicians got there first with CBGB, and this inspired the visual artists. Some attached themselves to the music scene while others paralleled the trends. There was an all-encompassing DIY spirit in downtown New York that spawned a deluge of artist run venues — galleries, magazines, clubs etc. For a brief moment in the early 1980s, it all coalesced into a flourishing East Village scene that rivaled in size and intensity the legendary EV of 20 years before.

What we now call punk visual art was a part of this. But it was an amorphous aesthetic that could never be easily defined and over time continually evolved. I track part of the story on my website 98bowery.com, which is named after the address where I lived from 1969 – 89. The site basically tells my story, but since the place and time was right, it’s also a lens on the broader tale. One can trace the evolution of punk visual art in three publications that I’ve posted on the site: the catalogue for the “Lives” show at the Fine Arts Building (1975); the catalogue for the exhibit “Punk Art” in Washington DC (1978), and the book ABC No Rio Dinero, The Story of a Lower East Side Art Gallery (1985).

“Lives” marked the curatorial debut of Jeffrey Deitch, who last year mounted the controversial exhibition “Art in the Streets” in Los Angeles. In some ways, “Lives” had a conventional take on art featuring work by conceptual artists looking for careers in galleries. What made the show unique was that the artists selected by Jeffrey involved themselves via performance, photography, and expressionistic drawings with real life issues like sexuality and politics. It fit in perfectly with the Fine Arts Building, which in the mid-1970s was a hot bed of experimental activity. In terms of music the building was an incubator for No Wave, and the site of the famous series of concerts that led to the No New York album produced by Brian Eno.

The ABC No Rio book that I co-edited with Alan Moore tells the story of the first five years of an alternative gallery that was founded when a group of artists illegally seized a boarded up city-owned building and mounted a show about real estate. A few months later the same group of artists were also involved with the notorious Time Square Show that took place in a former massage parlor. No Rio was the home of theme exhibitions like “Murder, Suicide, Junk.” It was originally a visual arts venue. The book ends in 1985 shortly before No Rio began hosting the punk music concerts that it’s famous for today.

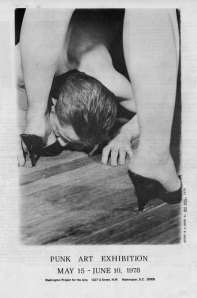

Readers of Visual Vitriol might be most interested in the Punk Art Show that Bettie Ringma and I organized in 1978 for the Washington Projects for the Arts. We called it “the world’s first punk art show” and if this claim is interpreted to refer simply to first using the term “punk art” in a mainstream art context, it might be accurate. The title was deliberately exploitative. Punk music was just getting noticed in the media and we figured why not take the hype and run with it. A lot of artists thought it was too blatant but it worked. The show got coverage all over the world and the phrase “punk art” has been in continuous use ever since. Hundreds of people now view the catalogue every day at 98bowery.com. Although it seemed very ad hoc at the time, the show provides a good cross-section of the punk visual aesthetic just as it was beginning in the US. We could not include everybody but the artists in the show were all major players in the scene and almost all are still active today.

Since your documentation began so early in the movement, how did you develop a curatorial sensibility for the work — did you base it on earlier experience with other art movements?

Almost everyone in the Punk Art exhibition was a regular at CBGB, which was still a small place with a very limited core group. Bettie and I were active in the art scene in Soho and Tribeca and saw right away that many of the people at CBGB were also visual artists. Those were the people we put in the show. It was almost a pre-selected exhibition. We just needed to refine things, which is what I think you mean when you ask about our “curatorial sensibility.” We tried not to be too narrow. There was a great deal of variety in the music that was being called Punk at the time and that was even truer about Punk visual art. We needed however to make sure that the show looked “Punk” for both the insiders and the outsiders. Definitely no “Pattern and Decoration” painters or “Greenbergian formalists” even if they were in a great band. What we ended up with was a mix rooted in subject matter, attitude, and social connections. It was different from most art movements, which were based around a single style or look. About the only real parallel was “Feminist Art,” which also coalesced around content and viewpoint. Ironically, when we mounted the Punk Art show in Amsterdam, a feminist art writer criticized it as macho art.

I assume the choices you made for the catalog and shows were governed by many factors. Could you walk us through the process of making some of those choices – why particular artists and pieces were chosen?

We couldn’t have done the exhibition without the cooperation of John Holmstrom, Legs McNeil and Punk Magazine. They were the ones who originally linked the word “punk” to music and in our mind they owned the word. Punk was a visual publication filled with John’s cartoons and photo stories directed by Legs along with photographer Roberta Bayley. Compared to our Soho art crowd, the artists at Punk were much more comfortable with the commercial side of art. They brought into the exhibition artists who worked directly with the music groups, most notably Arturo Vega, the art director for the Ramones.

Another lynchpin was Alan Vega (aka Alan Suicide) the lead singer of the group Suicide. In addition to making music, Alan was an exhibiting artist. His “junk” sculpture made out of malfunctioning electronic circuitry was the visual equivalent of Suicide’s aggressive electronic music. Here was a pure punk visual aesthetic without any overt references to the punk scene.

Probably our most difficult curatorial decision concerned Tom Otterness’s “Dog Shot” film. Tom was part of the artist group COLAB represented in the exhibition primarily through X Magazine. COLAB was later largely responsible for both ABC No Rio and the Times Square Show (where Tom was a principal organizer). The “Dog Shot” film is a major blot on Tom’s otherwise successful career as a public sculptor. It was a youthful misstep encouraged by the punk milieu of the times that he now wishes never happened. Essentially it’s a film loop showing him shooting a dog. A lot of punk at the time aimed to be provocative and there were many provocative pieces in the exhibition. Tom’s film was the most real and the most extreme. It definitely crossed a line. It’s in the catalogue, but after much arguing we didn’t include it in the show. I’m ready to defend it as art, but ultimately we couldn’t subject the Washington Project for the Arts to the intensely negative reaction that the film unleashes. Just doing a Punk Art show in 1978 was outrageous. I have an angry letter from Alice Denney, the director of the WPA, listing all the funding sources they lost because of the show.

To view Marc’s on-line archive, see here.